NAGC works to support those who enhance the growth and development of gifted and talented children through education, advocacy, community building, and research

Ann Robinson, Ph.D.

During the closing days of November, Native American Heritage Month, the story of Stuart Tonemah and his importance to gifted education is particularly timely. Stuart was a Native American advocate, administrator, educator, and scholar active in gifted education during the 1980s, 1990s, and the early 2000s. Stuart was a foundational figure in gifted education and influenced gifted education through federally funded projects and as a frequent consultant to the nation on both gifted education and Indian education affairs. He was of Kiowa/Comanche descent.

During the closing days of November, Native American Heritage Month, the story of Stuart Tonemah and his importance to gifted education is particularly timely. Stuart was a Native American advocate, administrator, educator, and scholar active in gifted education during the 1980s, 1990s, and the early 2000s. Stuart was a foundational figure in gifted education and influenced gifted education through federally funded projects and as a frequent consultant to the nation on both gifted education and Indian education affairs. He was of Kiowa/Comanche descent.

Stuart A. Tonemah was born in Lawton, Oklahoma in 1941 and graduated from high school there. He went on to Cameron University where he played college football and was on the Cameron Aggies team that won the Junior College Rose Bowl in 1961. Known as Golden Toes Tonemah, Stuart kicked an important field goal in the game as reported in the Aggies archives. He was talented in many domains and sport was one of them.

Stuart attended the University of Oklahoma and later pursued doctoral studies at Penn State where a number of students from one Kiowa elementary school were inspired to study. He left Pennsylvania to join the faculty of the famed Haskell Indian College in Lawrence, Kansas.

Stuart spent much of his professional life in academic settings. He was appointed the first director of the Native American Program at Dartmouth College in 1971. There, he distinguished himself as a successful and dignified advocate who was able to convince the Dartmouth administration to act on several requests from the Native American student community—increased Native American faculty and productive attitudinal changes in the college administration. In the 1970s, when sports iconography often used Indian themes, Stuart was not able to persuade Dartmouth leaders to change team mascots and cheers, but he argued eloquently and forcefully for such changes in campus publications. The college publications are filled with Stuart making his case and letters-to-the-editor responses.

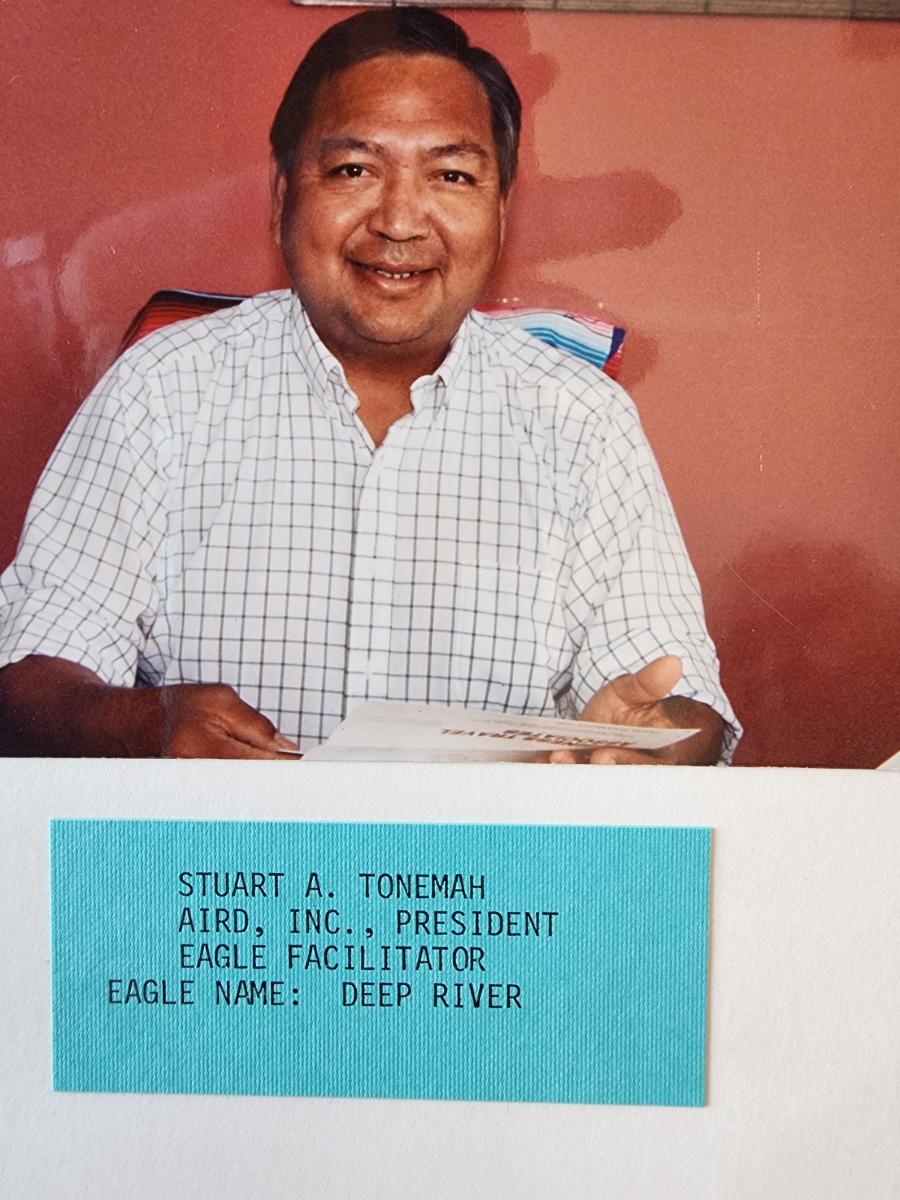

In the 1980s, Stuart established a non-profit, American Indian Research and Development (AIRD). It would prove to be instrumental in his goals for developing the talents of Native American students and their teachers. Three of his projects capture the breadth of Stuart’s vision and the sustainability of his leadership across decades.

First, he developed Explorations in Creativity (EIC), a program funded by the U. S. Department of Education and administered through AIRD. Stuart situated EIC, a four-week summer camp, at the Riverside Indian School near Anadarko, Oklahoma which first opened its doors in 1875. As one of four remaining Bureau of Indian Education boarding schools external to a reservation, Riverside offered the housing, kitchens, a space that allowed EIC to be an extended camp for Native American students from all over the United States including Alaska. Photos of EIC participants show emerging adolescents and adolescents in the performing and fine arts, discussing Indian philosophy, filming artisans like basketweavers at work, and lined up for early morning fun runs with Stuart himself. EIC was a family affair: Stuart’s youngest daughter attended EIC as a participant and his eldest daughter was pressed into camp counselor service. Over 40 years later, alumnae of EIC participate in a Facebook page which keeps them connected with one another.

Second, Stuart developed Project EAGLE, Effective Activities for Gifted Leadership Education, described as a Saturday intervention for Indian adolescents in Grades 9 through 12 and their families. Although Project EAGLE is the subject of a journal publication, it comes alive when a lucky reader opens three perfectly preserved and labeled “scrapbooks” from the early 1990s. Inside are scrupulously labeled photographs, daily program agendas, student artwork, and a hand-illustrated map that shows the 15 existing and 2 future sites of Project EAGLE. They spread across the country like tenacious buffalo grass radiating out from Oklahoma to Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Minnesota, New Mexico, Arizona, and Oregon, with the two future sites in such diverse geographical settings as Montana and Louisiana. Photographs and agendas in these documentary treasures indicate that Stuart may have visited many or all of the sites himself.

Third, Stuart understood that teachers were critical to the success of gifted education in the Native American community. He saw them as the “next to the last piece of the puzzle.” Stuart acted accordingly and wrote, received, and administered a grant to prepare 30 Native American teachers through a masters degree in Gifted Education, the American Indian Teacher Training Program (AITTP). A whopping 28 of the 30 teachers completed the program. His success rate for candidate completion was phenomenal. And, again, his personal reach was deep and lasting— a lovely and poignant note from one of his AITTP graduates rests respectfully on a legacy website announcing his death in 2009.

Stuart’s scholarly work was ground-breaking in its day. He first tackled the issues of assessment and wrote convincingly that giftedness for Native Americans must include tribal and community knowledge as well as measures of academic prowess. Reviewing the syllabi of his teacher training program, we find evidence of his early work on the identification of talents among Native American students as well as his dedication to a curriculum that honored the Native American world view. His assessment model directly incorporated a scale to tap Tribal and Cultural Knowledge to be completed by tribal elders. He was a consultant to the influential 1991 federal report, National Excellence: The Case for Developing America’s Talent.

Stuart was a leader in the Indian education movement as well, serving as the presidentially appointed Executive Director of the National Advisory Council on Indian Education (NACIE) from 1977 to 1979 which advises the Secretary of Education and the Secretary of the Interior and as the president of the National Indian Education Association in 1979. He was recognized as the Indian Educator of the Year in 1980-1981.

I met Stuart Tonemah once, perhaps twice, at NAGC conferences. He was at the height of his leadership; I was new to the field. Perhaps sensing I was homesick for the seemingly limitless prairie and the fragrance of Wyoming sage, we stood in a conference room at a refreshment table and talked about the acquired taste for high plains habitat and the importance of being able to see long distances in a Western landscape. Decades on, my chance encounter with him over a conference snack table resonates. Later, I read his work and came to understand that his was--and is--a foundational voice in gifted education.

Ann Robinson, Ph.D. is Distinguished Professor and founder of the Jodie Mahony Center for Gifted Education at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock.

The views expressed here are not necessarily those of NAGC