NAGC works to support those who enhance the growth and development of gifted and talented children through education, advocacy, community building, and research

Dina Brulles

Dina Brulles

Celebration of the 2021 Hispanic Heritage Month reminds us in the field of gifted education to reflect on how past misunderstandings have led to new insights and an enlightened vision. We are now seeing stronger efforts and increased advocacy more than we ever did in the past. As a gifted education community, we must continually focus on developing procedures, practices, and professional learning opportunities for our teachers and school administrators. They need support in developing opportunities for our historically under-recognized gifted Hispanic youth in order to change past practices that have perpetuated underrepresentation of these students in gifted education. In this blog I will briefly highlight some figures and facts that draw light to the urgency of identifying, serving and supporting these students, and then suggest plans and actions to make this happen.

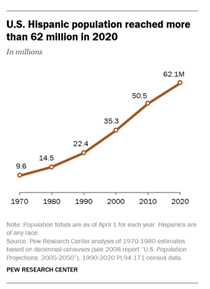

In 2020, the Hispanic population in the United States reached over 62 million, which accounts for 19% of the country’s population (Krogsrad, J.M. & Noe-Bustamente, 2021).

In 2020, the Hispanic population in the United States reached over 62 million, which accounts for 19% of the country’s population (Krogsrad, J.M. & Noe-Bustamente, 2021).

Looking at this general demographic data at a national level, let’s consider demographic representation from a few U.S. states. Hispanics are now the largest racial or ethnic group in California, accounting for approximately 40% of the state’s population. New Mexico (48%), Texas (39%), Arizona (32%), Florida (26%), and a rapidly growing number of states throughout the country, predominantly New York and New Jersey, yearly increase their Hispanic populations (Krogsrad, J.M. & Noe-Bustamente, 2021). Compare the general population to a school district’s gifted population in your area. How do these statistics equate in relation to the gifted population in your state? You can find answers to the “missingness” of different demographic groups in Access Denied/System Failure: Access, Equity, and Missingness in Gifted Education Status and Solutions, a 2021 report published by researchers Marcia Gentry, Gilman Whiting, and Anne Gray.

Given these facts and figures, how do we move toward making plans and taking action? We, in fact, know what we need to do and are learning our part in rectifying the inequities that have been ignored in our schools for far too long. Attention has been growing in recent years, much to the credit of scholars’ Jonathan Plucker, Scott J. Peters, and a slew of others’ work on closing achievement gaps (2016) and increasing attention to using local (and building) norms. We currently see increasing attention and service to diverse student groups, which includes more than 62 million Hispanic students in our nation’s schools. This is a staggering number, given that it represents almost half of Mexico’s entire population!

A very small percentage of teachers take pre-service coursework in gifted education because only a handful of states require it for teacher certification. Consider that an estimated 80-85% of teachers in the U.S. are white women, with the vast majority having no professional training in gifted education. Without this basic understanding of giftedness, one can see why (our schools’ predominantly white teachers) may miss seeing high potential in Hispanic students. They would have had to have familiarity with the Hispanic culture in addition to knowing what to look for when recognizing giftedness in general.

Reflect on the pipeline to school leadership. Some teachers become principals; some principals become school district administrators; and some district administrators become superintendents. Many of these school leaders make policies and decide programming and instruction, including in the design of their gifted services. While doing so, they may unknowingly and inadvertently add to the missingness of Hispanic students in gifted programs. Following this educator pipeline, we see that identifying and serving Hispanic gifted learners begins with professional learning for all educators in both understanding giftedness and in culturally responsive practices.

Educators sometimes hesitate to identify Hispanic students who are English language learners (ELL)—especially those who may have high ability but who are not yet achieving academically at levels commensurate with their ability because their schools’ gifted services are not designed to support learners from diverse populations. Broadening gifted services begins with an inclusive identification process. Once high potential has been identified, we must then ask ourselves how schools can better structure their gifted programs in ways that serve those identified from diverse populations (Peters & Brulles, 2018).

New identification processes designed to increase diversity of our gifted population, such as universal testing and the use of local norms, provide schools with new opportunities to support students who have previously been left out of gifted programs. School administrators must then plan for and respond to this movement by considering how to change systems and mindsets that previously prevented such progress. Progress requires cultural awareness and cultural competency. A shift in cultural perspective forces schools to outline new procedures that do not rely solely on characteristics of those historically served in gifted programs.

Now is the time to bring culturally relevant practices into our schools and culturally responsive teaching into our classrooms. This requires more than an occasional celebration based on a calendar event. It requires incorporating these ideas and perspectives into daily conversations and instruction (Johnson, 2021). The purpose is simply to enlighten and inform students about the cultures represented in our schools and in our world, as this recognizes students’ cultures and celebrates diversity. We achieve this by making connections to the students’ culture and language. By doing so we acknowledge, support, and encourage students, which can ultimately change their entire school trajectory (Brulles, Lansdowne & Naglieri, 2022).

The recognition described here helps build a sense of belonging many children with high ability desperately need. They know that they are smart; yet because of their language, their skin color, or their family customs, they are sometimes made to feel “different” and less valued than others in their classes. This feeling causes a tremendous load that can further hinder academic growth and impact social and emotional wellbeing.

Simple solutions to support these students can be to: 1) regularly include literature from diverse authors, voices, and perspectives while also including traditional literature typically found in schools; 2) provide cultural relevance that makes personal connections to the students; 3) learn more about the students’ cultures and traditions. These connections—asset-based pedagogy—can completely change how a child thinks and feels about her or him-self (Brulles, et al., 2022).

As a society, we find ourselves at a time of deep soul searching within the Black Lives Matter movement. This searching must extend to our Hispanic population. In recent years, researchers and professionals in the field have provided the data, the tools, and the resources that clearly expound upon and support the need. As school practitioners and leaders in gifted education, it is time to work together, and make it a priority to better identify and serve our gifted Hispanic learners.

Brulles, D., Lansdowne, K., Naglieri, J. (2022, pending publication) Using and Understanding the Naglieri General Ability Tests, Free Spirit Publishing, MN

Gentry, M., Gray, A., Whiting, G.W., Maeda, Y., & Pereira, N. (2019). Systems failure: Access denied. Purdue University, IN. https://www.education.purdue.edu/geri/new-publications/gifted-education-in-the-united-states/

Johnson, Alisa (2021) The Culturally Responsive Teacher, National Symposium on Equity for Black and Brown Students in Gifted Education, NAGC

Peters, S.J. & Brulles, D. (2017) Designing Gifted Education Programs and Services: From Purpose to Implementation. Prufrock Press, TX

Plucker, J. & Peters, S.J. (2016) Excellence Gaps in Education: Expanding Opportunities for Talented Students, Harvard Education Press, MA

Krogsrad, J.M. & Noe-Bustamente, L., (Sept. 9, 2021) Key Facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage Month, Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/09/09/key-facts-about-u-s-latinos-for-national-hispanic-heritage-month/

Dina Brulles, Ph.D., is the director of gifted education in Paradise Valley USD in Arizona as well as the Gifted Program Coordinator at Arizona State University. She also serves as NAGC's Governance Secretary and formerly as the board's School District Representative. Her work in these roles, along with her consulting and publications, emphasize and encourage inclusive identification practices and programming in gifted education.

The views expressed here are not necessarily those of NAGC.